HISTORY

Valley of The Horse

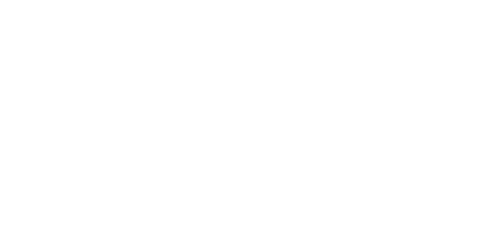

By the time the Queen’s great-grandfather, then Prince of Wales, set up the royal stud at Sandringham in 1886, Widden had been going nearly 20 years. To mark the stud’s centenary, Turf historian Douglas Barrie published Valley of Champions. ‘During the 19th century Australia, more than any other country on earth, needed good horses’ he wrote. ‘Australia became the proving ground for the English thoroughbred.’ It cost time and money to bring livestock across the world by sail, so far-sighted settlers imported the best they could afford – or bred from those that did. No one was more far-sighted than the Thompsons, who settled around the Widden Valley in the Upper Hunter.

John Thompson had arrived in the colony from Yorkshire in 1832, dreaming of being a wool king. But the dingoes slaughtered his merinos and so his sons concentrated on Shorthorn cattle and saddle horses well before they bought the present Widden property in 1867. There are cattle on the property to this day but it was horses that would make it famous. When the forerunner of the Australian Stud Book started in 1878, the Thompsons registered three ‘blood’ mares in it, soon adding more.

Those foundation mares began great thoroughbred families – and one of the world’s great studs. Now Widden is celebrating 150 years in the same family. It is one of few horse studs anywhere in the world that has always survived solely as a working farm. In racing, it’s the horses, trainers and jockeys that tend to be honoured, but when the Australian Racing Hall of Fame made its inaugural inductions in 2001, the Thompson family was chosen along with Phar Lap and Bart Cummings. Accolades don’t come much higher.

IN ANY BUSINESS, 150 YEARS IS A RARE FEAT.

Widden was established in the same decade as both the Melbourne Cup and, the iconic Australian brand, Arnott’s. It is as old as the AJC’s land grant at Randwick and older than Australian Test cricket, which started in 1877, and has evolved to be at the top of its game. Significantly, Widden is as old as the Inglis bloodstock business, and the histories of the agents and the stud have been entwined since they began.

In the 2014/15 racing season, Widden-bred horses won ten per cent of Australia’s Group One races. Among the winners was Dissident, Australian Horse of the Year. Last season, Widden was the leading sales vendor of Group One winners. As someone once said, ‘those born on this soil have won all there is to win’. When Widden’s 150th draft of yearlings left the valley for the Easter sale in Sydney in late March, 2017, they took the four-hour journey from the Pastoral Age into the 21st century.

It’s easier these days, with bitumen roads, cattle grids and bridges where there used to be buggy tracks and boggy fords. Even in living memory, there were 22 gates and a dozen creek crossings on the Widden road, winding through the valley from the entrance.

When a young Englishman arrived to work at Widden in 1977, he hitched a ride from Denman to the Widden turn-off. He assumed the homestead would be an easy walk. He hadn’t got far when a vehicle came along – it was his new employer ‘Bim’ Thompson, who told him it was 15 kilometres in to the house and stables.

The young man was Henry Plumptre, just one of many names in thoroughbred breeding to have honed their skills at Widden. Plumptre still thinks himself lucky to have handled the phenomenal Vain, the horse he rates the most magnificent stallion he has known – and the one with the sweetest tooth. The mighty chestnut would do anything for a peppermint.

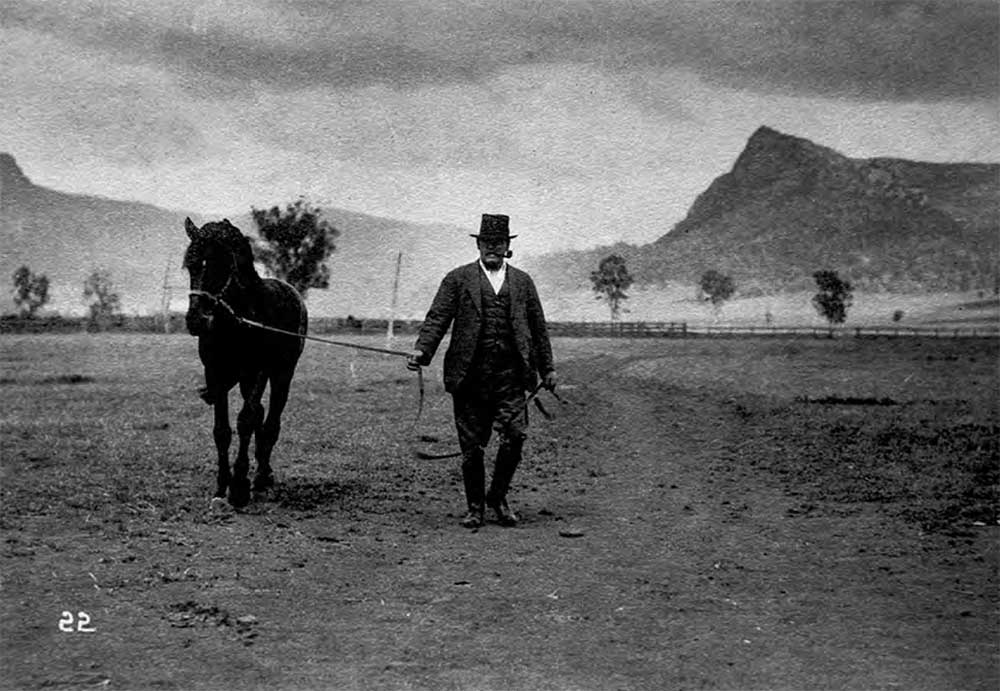

Vain is one of a string of champions to have enjoyed life in the valley. Antony Thompson remembers Vain well but his earliest memory is of the day Todman died. He was only four years old but recalls how sombre it was the day the great stallion was laid to rest beside his legendary sire, Star Kingdom.

At 45, Thompson is the seventh generation of the family to breed horses in the valley. So when the 150th draft was set to leave, he was there to oversee it. Making history is all in a day’s work.

In Queen Victoria’s time, Widden stockmen drove mobs of young horses to market, much like cattle. Later, they would lead them the 60-odd kilometres to Denman, one yearling each side of a hack. After a spell on a satellite property, the yearlings would be railed to Newmarket, two months before the sales. Now, all but the last week of ‘prep’ is done on the farm and the trip is done with a fleet of trucks.

They arrive before sunrise, crossing the creek between the homestead and stallion paddocks. The valley is perfectly quiet at night: nothing but brilliant starlight gets past the sandstone bluffs bordering the surrounding bush land – more than a million wild acres, hardly changed in a million years.

A yearling whinnies, stable lights flicker on and the cream of Widden’s yearlings are led out one by one ready to join the outside world. These youngsters know nothing beyond the broad creek flats in the ranges. They have never seen or heard traffic, trains or jet planes – nothing louder than tractors or the squawking cockatoos that pinch leftover horse feed.

How they handle the transition of the next few days is the first test they’ll face on the way to the biggest test of all, the racetrack. David Merrick, stud manager, watches each yearling being led up the ramp the way they have learned on practice runs around the property. Not one of them jibs, proof of good handling.

Merrick and his staff have cherished these and many others since they were foaled. He and Widden’s general manager of 30 years, Derek Field, have seen a dozen generations of great thoroughbred families come and go. It’s an addictive business, with the ingredients of a drama serial: winning and losing, life and death, grit and generosity – and the rise and fall of dynasties, both horse and human.

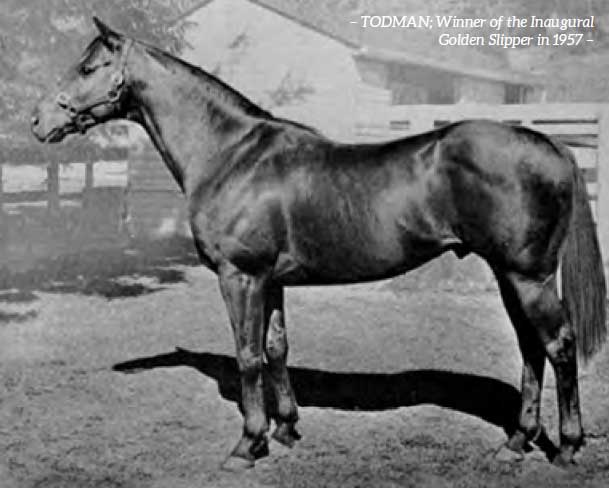

The two men’s careers span an extraordinary time, from the end of the era of ‘colonial’ and ‘imported’ sires serving their 40 or 50 mares a year to a global industry of jet-setting shuttle stallions speed dating 400 mares a year in two hemispheres. Merrick saw Marscay foaled at Woodlands – and saw his last days at Widden, where he is buried with Bletchingly and other great ones whose oil paintings hang in the boardroom in the new sandstone office. ‘You still see his blood getting about,’ Merrick adds, speaking of the rugged son of Biscay and grandson of the daddy of them all, the legendary Star Kingdom, buried next door at Baramul. He could say more but is busy just now with more than $7 million dollars worth of superb horseflesh. It sounds a lot but is only a quarter of what Widden’s latest top gun, Sebring, cost to head the present roster of eight sires, with Zoustar not far behind.

THROUGH DROUGHT AND DEPRESSION, BUSHFIRES AND BUSHRANGERS, THOMPSONS HAVE BRED THOUSANDS OF HORSES HERE.

Not just many of Australia’s finest gallopers but some of the best in the world. The legendary Ajax dominated the late 1930s era the way Winx dominates this one. For the Thompsons, he still shades Kingston Town, bred here in the same rustic breeding shed where Black Caviar had her moment with Sebring in 2014. Cup winners and classics winners have all come from, or to, this patch of paradise. But it is Golden Slipper winners the valley is known for. In the Slipper’s 60-year history, the journey has started in the Widden Valley more than anywhere else.

Not just many of Australia’s finest gallopers but some of the best in the world. The legendary Ajax dominated the late 1930s era the way Winx dominates this one. For the Thompsons, he still shades Kingston Town, bred here in the same rustic breeding shed where Black Caviar had her moment with Sebring in 2014. Cup winners and classics winners have all come from, or to, this patch of paradise. But it is Golden Slipper winners the valley is known for. In the Slipper’s 60-year history, the journey has started in the Widden Valley more than anywhere else.

No other stud has its record for making Golden Slipper winners into successful sires. And Todman, Vain, Marscay and Stratum all produced winners of the race as well. Vain and Marscay have two of the 16 headstones commemorating Widden’s greats. Here, too, are Lunchtime, General Nediyim, Salieri and Delta. So is Ajax’s dam, Medmenham. Ajax was sold to America, eventually to Bing Crosby. The ivy on the Widden homestead came from a cutting brought back from his stable in California.

The Widden yearlings of 2017 are as big, bold and beautiful as expert hands can make them: the product of 400 years of breeding and 18 months of feeding. Widden brands more than 100 foals a year, some for clients. On pedigree, conformation and ‘presence’, the 31 headed for one sale are typical of the 80 or so yearlings the stud sells each year. They are full of hard feed and nervous energy – the shared characteristic funneled down to the modern racehorse through a handful of common ancestors: the Darley Arabian to Eclipse, St Simon to Northern Dancer.

These young aristocrats all share the genes for speed and stamina, a finely calibrated combination of blood, bone and muscle enhanced with scientific diet and some of the best natural horse country on Earth. They are born to run – and for the will to win that makes racehorses try.

Call it character. Call it heart. It’s a mystery that buyers will be trying to decode when these colts and fillies step into the ring the week after leaving the farm. Antony compares yearlings to 12-year-old kids skylarking at the beach: they’re old enough to show athletic promise – but ‘you can’t tell which ones will try.’ He’s as wary as any parent of picking a favourite child but he likes a bay filly out of an American-bred mare.

The filly is not just well bred and well made but well marked, with a neat star between intelligent eyes and not another white hair on her. But on this otherwise perfect Sunday evening, something catches Antony’s eye. He steps into the filly’s loosebox and runs his hand over her near shoulder. On the silky skin under the famous brand, JT over lazy 2, he finds some tiny bumps, probably insect bites. He asks the filly’s handler to treat them.

The bites mean little to a horse – but at this rarefied end of the breeding business, this is not just a horse. She’s a princess making her debut. Any tiny blemish is as about welcome as pimples on a supermodel before a fashion show. It would be easy to obsess about such fragile creatures but Thompson grew up knowing that for all the fabulous prices and famous names, horses are livestock.

Widden is beautiful but not because of money lavished on luxuries. There are no helicopters, limousines or pretensions. Tradesmen and fencers say they like working here because the boss turns up in his well-used Toyota with a few beers at the end of the day. Sometimes he takes visitors up the foothills rising over the loamy flats, to where limestone pokes through the red dirt – which explains the good bone Widden horses have.

On an autumn afternoon after good rains, ’roos and wallabies come out to graze on fresh growth and black cockatoos and king parrots drift past, the dying light catching slow-moving wings. At the southern end of the valley are the ‘Cat’s Ears’, twin hills that look exactly as they’re named. Smaller valleys snake into the Wollemi Park wilderness either side of the ‘cat’. ‘Banjo’ Paterson, who watched plenty of Widden horses race during his long life, coined famous lines about sunlit plains and rugged battlements and the glory of everlasting stars. As afternoon becomes night up here, those images come true. The valley of the horse has all that and a creek as well. It’s Eden with gum trees.

The Thompsons have always been horse farmers rather than horse fanciers. Like their friend and competitor in New Zealand, Sir Patrick Hogan, they’ve relied on the stock they produce and the stallions they stand.

TO SURVIVE SO LONG IS AN ACHIEVEMENT. TO THRIVE IS ASTONISHING.

A century ago, various Thompson family members between them bred a third of yearlings sold at the 1917 Easter sales. That dominance would alter as the industry expanded but Widden has always turned out many of Australia’s best horses each season. Since Antony took the reins in 1993, at 21, Widden’s future has rested largely with him. Each of his forebears was part of a continuum, learning from preceding generations all the way back to the original pioneer Thompson. But when Antony and his sisters lost their father ‘Bim’ in an accident before his eighth birthday, in 1980, it could easily have ended the family connection with Widden. As it was, a board of trustees kept the stud going while the children finished school.

‘Bim’, real name James, was an outstanding horseman in a family full of them. He once aimed to ride at the 1964 Olympics but had to abandon that dream to return to Widden after his father, Frank Thompson, was hurt in a car crash. Antony grew up with stories about his father and grandfather. Showing visitors around the older bits of the rambling homestead, he points to a picture of a horse called Crispian winning at Muswellbrook in 1971. Crispian’s rider that day (in the Widden colours: orange with purple cap) looked very happy – and very big. That’s because it is ‘Bim’, who had engineered a way to ride his own horse when its regular professional jockey did not turn up on time. He weighed in at 13 stone 4, or 84 kilograms. Weight will stop a train but it didn’t stop Crispian winning the open-class sprint with his delighted owner in the saddle. ‘He was a proper horse, all right – Dad got his perfect record of one race ride for one win,’ says Antony, recounting how furious stewards warned his swashbuckling father never to pull such a brazen stunt again. It would never happen now but racing still had a touch of Banjo Paterson colour then. The story shows how ‘hands on’ the Thompsons were – and are.

Antony prepared thoroughly for his life’s work in the family ‘firm’. When he left school at 17, his education began first as a jackaroo on Glen Rock cattle station on Barrington Tops. There he learned to ride – and shoe – rough horses picked from a mob of 100. After six months he went to Ra Ora stud in New Zealand, then to Sydney trainer John Morish. He spent a season with the astute Patrick Hogan at his famous Cambridge Stud, in time to see Sir Tristram at his peak. Then he worked for a London bloodstock agent and a Kentucky horse farm.

Those three years away, learning from the best, let him see his inheritance with clear eyes – and judge what changes would let Widden match corporate international breeders taking over Australia’s old studs. He took advice from shrewd businessman and breeder, Jack Ingham, who told him breeding was a young man’s game and that if he waited until he could afford it, it might be too late. So he borrowed to invest in stallions, broodmares and the endless list of improvements needed to stay competitive.

He and his wife Katie have kept at it. In good years, the farm gets new fences built, more trees planted. There’s the new office, new yearling barns and parade area. The 1885 homestead has been extended and modernised for the third time in a century. Its new kitchen window has a stunning view of ‘the cat’s ears’. The mantel above the stove is a weathered ironbark beam Antony rescuedfrom a ‘bushranger’s hut’ in the hills shortly before it burned down in a bushfire. Bushrangers are part of Widden lore. The Thompsons grow up knowing Thunderbolt’s Cave overlooking the valley, where Frederick ‘Captain Thunderbolt’ Ward hid in the 1860s. The colonial novelist ‘Rolfe Boldrewood’, once the local magistrate, based his fictional bushrangers’ hideout (‘Terrible Hollow’ in Robbery Under Arms) on a remote part of the valley.

The sandstone office echoes the stone ‘old church’ still used as a stallion shelter since a fire gutted it in 1904. The replacement ‘new church’ built that year, from hand-hewn timber, is still used to this day. The 21st century is edging into the valley. The old rail fences can no longer be replaced with local bush timber, so horse paddocks are being re-fenced with rubber compound posts and unbreakable ‘horse rail’, flexible strapping with a built-in electric wire. It’s as modern as the solar panels on the barn roofs. So is the quarantine area built well away from the stallions, permanent broodmares and young stock. New arrivals are kept here after being unloaded at one of the custom-built bays made to suit every size truck and float. ‘The float drivers say it’s the best place of any to unload,’ says the man who planned it. In the end, it’s about doing what’s best for the horses. It has been that way for seven generations.